In Conversation with: Dean Simon Chesterman

In Conversation with: Dean Simon Chesterman

Insight MinLaw goes behind the scenes to uncover stories about how the work we do impacts you.

Professor Simon Chesterman, Dean of the National University of Singapore Faculty of Law (NUS Law) and Senior Director of AI Governance at AI Singapore, is a recognised authority on international law, whose work has opened up new areas of research on conceptions of public authority, the changing role of intelligence agencies, and the emerging role of artificial intelligence and big data.

Simon is also the author of four young adult fiction novels including the Raising Arcadia trilogy.

In Letters of the Law, a collection of letters written by authors from the legal industry, Simon wrote a letter addressed to his younger self, during the year he spent studying Chinese at the Beijing No. 2 Foreign Languages Institute before returning to start university in Australia.

Insight MinLaw caught up with Simon to chat about AI, legal education and his novels.

Insight MinLaw: In your recent book, We, the Robots? Regulating Artificial Intelligence and the Limits of the Law, you examined how laws are dealing with AI. What is the impact of AI on the legal profession?

Simon: The idea that legal practice — seen as the logical application of rules to established facts — could be automated has been around for decades.

In the 1980s, researchers developed prototype systems of rules in machine-readable form. The enthusiasm was characteristic of the time, preceding as it did one of the “AI winters” that periodically saw inflated expectations crash against reality.

Subsequent decades did see transformations in legal research and document management. These increased lawyers’ access to information and their efficiency in using and sharing it, but did not fundamentally alter their role.

Even those encouraging the adoption of technology believed that the inability of AI to emulate human qualities limited its scope for taking on the higher functions of lawyers — the role of judges in particular.

As we have seen in other areas, however, emulating human methods may not be the right or the best approach for reaping the benefits of AI. Autonomous vehicles, to pick an obvious case, are not driven by humanoid robots controlling speed and direction with mechanical hands and feet in substitution of their absent “drivers”.

The DoNotPay chatbot, launched in 2015, offered an indication of what might be possible. Written by a 17-year-old Stanford student, it followed a series of rules to appeal against parking fines. Similar technology now facilitates other simple tasks from the making of wills to reporting suspected discrimination, yielding efficiencies as well as offering greater access to basic legal services for the wider public.

Many lawyers long assumed that litigation would be the last part of legal practice to be automated. Yet, online dispute resolution (ODR) has been around since the 1990s and, for smaller claims in particular, has been embraced not only by online traders like eBay and PayPal, but also in the legal systems of Canada and Britain.

At its simplest, ODR merely helps parties settle their own disputes more efficiently. An algorithm might, for example, serve as the go-between to parties as they negotiate a settlement, nudging them until they reach a mutually acceptable result. A more elaborate system might analyse relevant data and propose its own settlement. In either case, the outcome is binding because the parties themselves agree to it.

Deeper inroads have been made in China.

In late 2019, Hangzhou’s Internet Court began allowing parties to appear virtually before an avatar judge. The avatar can handle online trade disputes, copyright cases, and e-commerce product liability claims. Hangzhou was chosen because it is the home of Alibaba, enabling integration with trading platforms like Taobao for the purpose of evidence gathering as well as ‘technical support’. Meanwhile, the Wujiang District of Suzhou has trialled a “one-click” summary judgment process for less complex criminal cases, automatically generating proposed grounds of decision complete with sentence.

Singapore’s Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon has said that such developments in China are making “machine-assisted court adjudication a reality”. At the same time, he noted, the use of AI within the justice system gives rise to a “unique set of ethical concerns, including those relating to credibility, transparency and accountability”.

To this one might add considerations of equity, since the drive towards greater automation is being dominated by deep-pocketed clients and ever-closer ties to technology companies, with uncertain consequences for the future administration of justice.

Insight MinLaw: What qualities do you think law students need to succeed in their careers?

Simon: I’ll take it as given that our students need to be bright, to know the law, to have critical and analytical skills, to be able to communicate and to persuade. Above and beyond these, they need to be able to cross boundaries: literal, metaphorical, and social.

In terms of literal boundaries, half of our students in a normal year spend a semester or more on exchange, some earning a Master’s degree in their fourth year through partnerships with New York University, King’s College London, and other leading schools. The rest benefit from the diverse students from around the world who join our upper years. We are nonetheless exploring additional ways for students to travel for shorter periods, in particular exposing them to jurisdictions in Asia.

For too long, Singaporean law students look to the West when they looked abroad. I think more and more are realizing the importance of understanding our own backyard.

By metaphorical boundaries, I mean disciplinary ones. There’s a dirty secret many law students hide, which is that they studied law because they were bright but didn’t like numbers or didn’t like blood. Increasingly, however, technology is accepted as a vital area of practice and a dynamic force that is changing practice itself (as I described above). Right now we are engaged in a curriculum review that will increase exposure of our students to technology, but also to numbers. Not so much to blood as yet.

As for social boundaries, I do think it’s vital that our graduates can relate to people from all walks of life.

The 2019 NUS Law Rag team with Professor Simon Chesterman. Photo taken before COVID-19. (Credit: NUS Law)

The 2019 NUS Law Rag team with Professor Simon Chesterman. Photo taken before COVID-19. (Credit: NUS Law)

We’ve tried to address this in terms of our intake, by increasing aptitude-based admissions (formerly discretionary admissions). Earlier this year, we launched a pilot programme where candidates whose achievements put them in the top five per cent of students at any of Singapore’s junior colleges and Millennia Institute, based on their GCE ‘A’ Level results, International Baccalaureate (IB) Diploma or equivalent, are eligible for shortlisting to sit for the written test and interview.

We’ve also sought to address it through requiring all of our students to do pro bono service during law school. The minimum of 20 hours is not particularly onerous, but gives them a chance to see law in practice as well as law in the books, as well as introducing them to clients whom they might not normally have encountered. In this way, we hope, we can plant the seed that the value of a lawyer isn’t measured in billable hours or a paycheque, but in people helped.

Insight MinLaw: In the letter to younger self, you wrote that lawyers have a chasm that separates their head from their heart, how can we get lawyers to be more empathetic?

Simon: I’m not sure you can “make” someone more empathetic, particularly once they’re an adult. Hopefully the pro bono work that our students do helps them to see the importance of law as a force for good.

One positive indication is that some naysayers warned when we started the pro bono programme that the 20-hour requirement would be a ceiling as well as a floor. In other words, students would do their 20 hours and then stop. Happily, the average number of hours completed is more like 50 – with many students doing far more than that. This gives me hope that perhaps I was wrong about that chasm.

Insight MinLaw: What inspired you to write fiction?

Simon: I’ve always been an avid reader and had dabbled in fiction as a teenager. (In fact, I completed two unpublished – and unpublishable – novels.)

When encouraging my own children to read, it rekindled that interest in writing. My Raising Arcadia trilogy in particular was an attempt to show my own kids that you could have a strong female character who succeeded through her brains rather than, say, magic or violence.

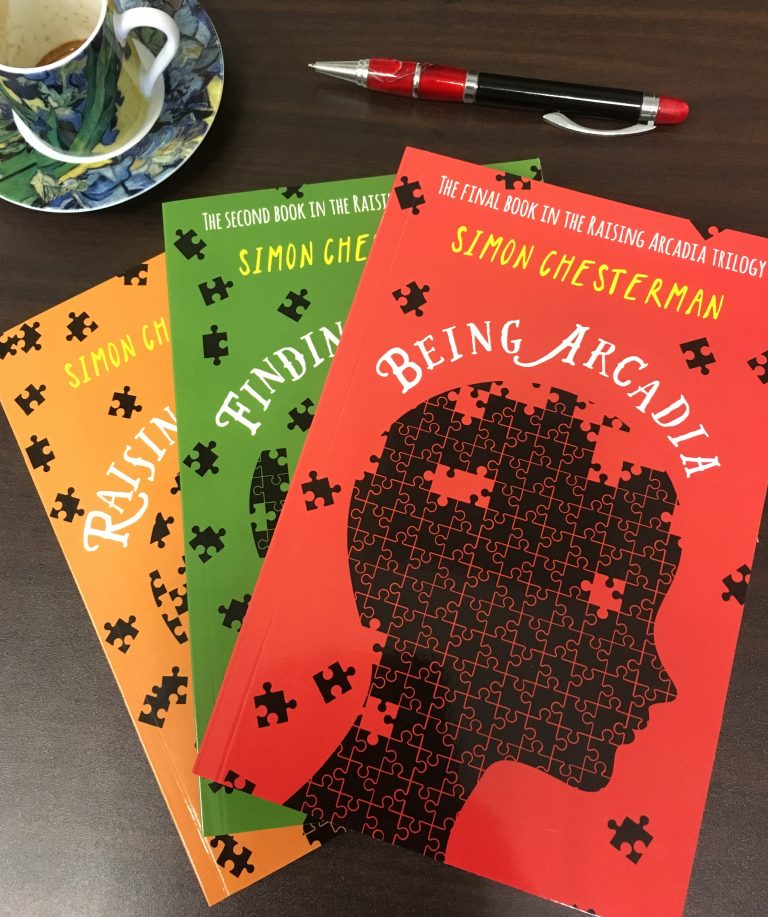

The Raising Arcadia Trilogy (Credit: Simon Chesterman)

The Raising Arcadia Trilogy (Credit: Simon Chesterman)

I suppose another reason was that my kids — bizarrely — seemed to have no interest in reading about international law or data protection. So at least these were books of mine that they would read.

Insight MinLaw: Complete this sentence – Dear Future Self,

Simon: So, did you ever get that sabbatical? Just curious.

Last updated on 27 October 2021

Other stories you may like:

In Conversation with: Dean Leslie Chew

The Rise of Legal Technology